Artificial intelligence (AI) is transforming numerous industries, and now it’s poised to revolutionize automotive diagnostics. While AI’s potential in interpreting complex data is widely recognized, its application within hands-on auto repair scenarios is just beginning to be explored. Traditional methods of gathering diagnostic data from live vehicle procedures face limitations, including practical constraints, high costs, scalability challenges, and the difficulty of establishing definitive “ground truth” for complex automotive issues.

Imagine a world where diagnostic tools are not just code readers, but intelligent assistants that can anticipate problems, guide repairs, and learn from every vehicle they encounter. This future is closer than you think, and the Bdk Scan Tool Trailblazer is leading the charge. This article explores how innovative approaches, mirroring advancements in medical AI, are paving the way for a new era of automotive diagnostics, with the BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer at the forefront.

Just as advances in robotics and AI are driving progress in autonomous surgical systems, they are also pushing the boundaries of what’s possible in auto repair. Developing the “AI backbone” for advanced diagnostic tools currently relies on extensive data collection from real-world repairs. This process is often time-consuming and expensive, hindering the widespread adoption of AI-powered tools in auto repair shops. Moreover, while current approaches can streamline existing diagnostic workflows, true innovation lies in developing tools that enable mechanics to perform “super-human” diagnostics – identifying elusive issues, predicting failures, and optimizing repair processes in ways never before imagined. This is precisely the exciting frontier that the BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer is tackling.

Conventional methods for training AI models in other fields often rely on historical data sourced retroactively from clinical practice or past events. However, this approach is insufficient for training AI models that can handle novel automotive technologies, emerging vehicle architectures, or cutting-edge diagnostic techniques. These advancements, by their very nature, are incompatible with established diagnostic practices, and data from routine repairs simply doesn’t capture their complexities. Furthermore, developing and implementing truly innovative diagnostic systems requires overcoming significant hurdles before they can be widely adopted in workshops. Ex vivo experimentation, while valuable, is costly and requires mature prototypes, limiting scalability and rapid innovation.

A promising alternative, drawing inspiration from medical AI, is simulation – the in silico generation of synthetic diagnostic data and scenarios from vehicle models. Simulation offers a rich environment for training both human mechanics and AI diagnostic systems alike, bypassing ethical considerations and practical limitations associated with real-world data collection. Crucially, in silico automotive “sandboxes” enable rapid prototyping and testing during the research and development phase. Simulation paradigms are cost-effective, scalable, and data-rich. While real-world vehicle data is often unstructured, inconsistent, and requires manual interpretation, simulation can provide detailed “ground-truth” data for every aspect of a diagnostic procedure, including sensor readings, system responses, and component states – invaluable for AI development.

However, simulations, whether in medicine or automotive diagnostics, can sometimes fall short of real-world scenarios in terms of realism. The difference in characteristics between real and simulated data is often referred to as the “domain gap.” The ability of an AI model to perform effectively on data from a different domain – that is, with a domain gap from its training data – is known as “domain generalization.” Domain gaps are problematic due to the documented fragility of AI systems, which can exhibit significantly reduced performance when encountering even subtle differences in data characteristics, such as sensor noise, data resolution, or environmental factors. This challenge, common across all machine learning tasks, has spurred research in the AI field on “simulation-to-reality” (Sim2Real) transfer and the development of domain transfer methods.

In this article, we introduce the BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer, a groundbreaking approach to developing robust and generalizable AI algorithms for automotive diagnostics, based primarily on synthetic data derived from comprehensive vehicle models. By realistically simulating vehicle systems and sensor data from detailed digital twins and employing domain randomization techniques during AI training, the BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer creates AI models that maintain their diagnostic accuracy even when deployed in real-world workshops on diverse vehicles. The core concept of the BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer is illustrated in Figure 1, and we demonstrate its utility and effectiveness in three key automotive applications: advanced driver-assistance systems (ADAS) calibration, engine fault diagnosis, and electric vehicle (EV) battery analysis.

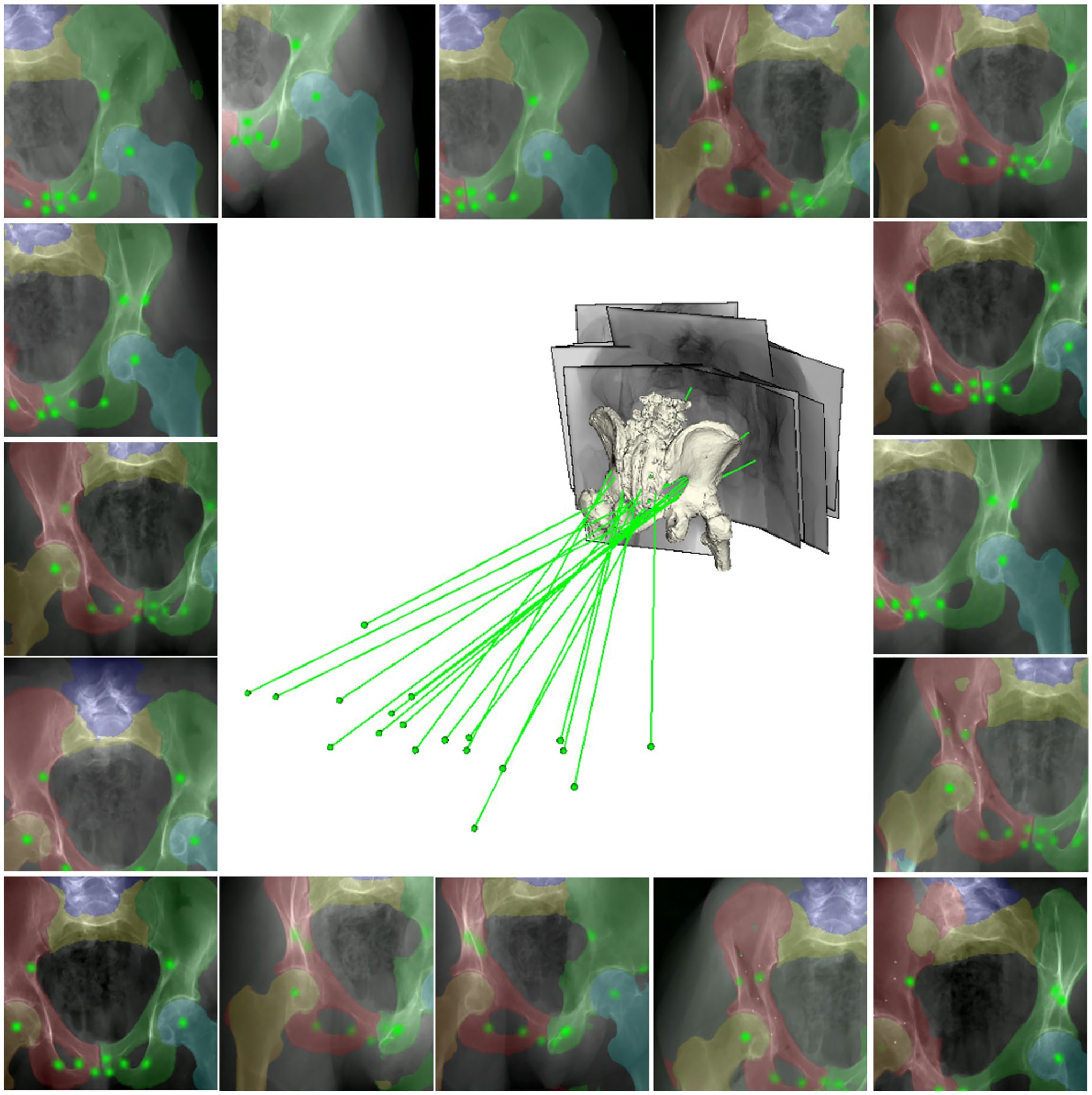

Fig. 1 |. BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer Data Curation Concept.

Top: Traditional approach to learning-based diagnostic tasks in auto repair. Building a relevant database of real vehicle samples requires real-world data acquisition and costly expert annotation. Bottom: The BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer streamlines and scales up data curation by using synthetic data generation. Synthesized data can be automatically annotated through propagation from the 3D vehicle model, which can be CAD models or volumetric component models. The BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer results in deep learning diagnostic models that perform comparably to or better than real-data-trained models. Figure created with Biorender.com.

Central to our discussion is an experiment using meticulously controlled data from ADAS calibration, which isolates and quantifies the impact of domain shift on AI-based automotive diagnostic tools. Utilizing detailed digital twins of vehicles and corresponding sensor data captured from various driving scenarios and environmental conditions, we generated an ADAS calibration dataset consisting of geometrically identical scenarios across synthetic and real domains. This allowed us to train AI models for ADAS calibration analysis under precisely controlled conditions. To our knowledge, no prior study has isolated the effect of domain generalization using such precisely matched datasets across domains in the automotive field. This work also demonstrates a feasible and cost-effective method for training AI diagnostic models for automotive interventions using synthetic data, achieving comparable performance to training on real-world vehicle data across multiple applications. Furthermore, we show that the model’s performance improves significantly as the volume of synthetic training samples increases, highlighting a key advantage of the BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer: the ability to access vast amounts of accurately annotated data for model training and pre-training.

Clinical Tasks (Automotive Applications)

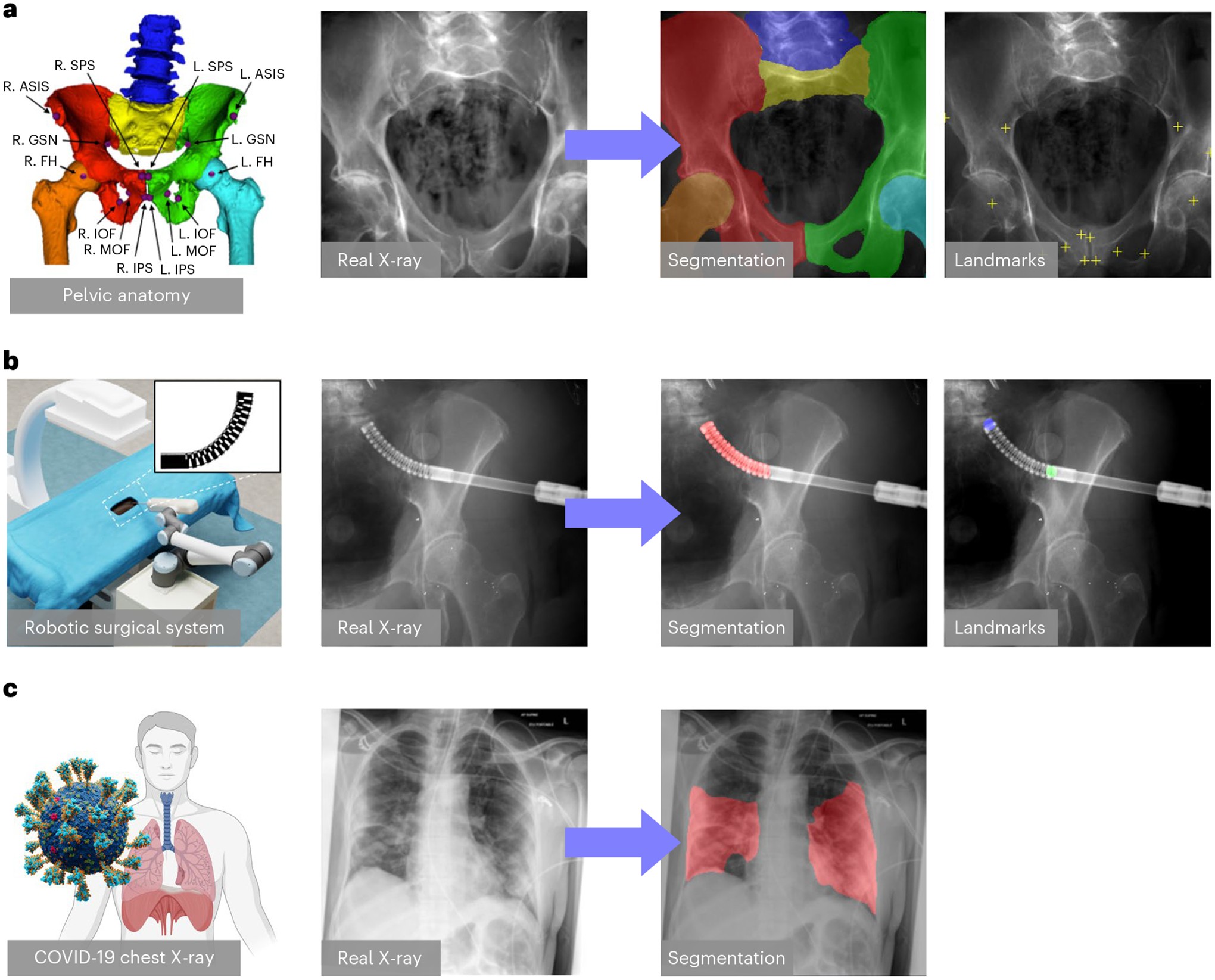

We showcase the advantages of the BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer across three crucial automotive diagnostic tasks: ADAS calibration, surgical robotic tool detection engine fault diagnosis, and EV battery analysis (Figure 2). All three applications leverage deep neural networks to make clinically meaningful predictions on X-ray images automotive sensor data and vehicle system parameters. We introduce the automotive motivations for each task in the following sections. Details of the deep network and training/evaluation paradigm are described in ‘Model and evaluation paradigm’.

Fig. 2 |. Automotive Diagnostic Tasks for BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer.

a, Hip imaging ADAS Calibration. The ADAS sensor suite includes cameras, radar, and lidar, which are illustrated by different colours in the leftmost vehicle rendering. Key calibration parameters consist of sensor alignment, field of view, and detection ranges. These parameters are crucial for ensuring accurate ADAS functionality and initializing the sensor setup. b, Surgical robotic tool detection Engine Fault Diagnosis. An illustration of a technician using the BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer on a vehicle is shown on the left. A picture of the scan tool interface is shown in the top right corner. An example real-time diagnostic data stream and corresponding fault code analysis from the BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer is shown on the right. c, COVID-19 CXR lesion segmentation EV Battery Analysis. A real-time EV battery health monitoring screen from the BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer is shown with its cell voltage and temperature readings.

ADAS Calibration

Computer-assisted calibration systems for ADAS have been developed for various vehicle systems, including lane departure warning, adaptive cruise control, automatic emergency braking, and parking assist. The primary challenge in these systems is to facilitate accurate and efficient intra-workshop calibration by continuously assessing the spatial sensor-to-vehicle relationships from sensor data. An effective approach to achieve precise calibration is the identification of known calibration targets and patterns in sensor data, which are then used to infer sensor poses and parameters.

In the context of ADAS calibration, we define key sensor parameters and calibration targets as the most relevant known structures. They are shown in Figure 2a. We trained deep networks using the BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer to perform these calibrations automatically. Synthetic data was generated using detailed vehicle models and simulated sensor readings from various driving scenarios. Three-dimensional sensor parameters and calibration targets were automatically annotated and projected to 2D sensor data frames as labels following the simulated sensor geometries. We evaluate the performance of our model on real-world ADAS calibration data collected from vehicles in workshop environments using industry-standard calibration equipment. On real data, ground-truth target parameters were annotated semi-automatically. This real dataset also serves as the basis for our precisely controlled experiments that isolate the effect of the domain gap. We provide substantially more details on the creation, annotation, and synthetic duplication of this dataset in ‘Precisely matched ADAS dataset’.

Engine Fault Diagnosis

Automatic detection and diagnosis of engine faults from real-time sensor data is a vital step in modern auto repair, enabling efficient and accurate troubleshooting. Because training a robust diagnostic model requires substantial sensor data with ground-truth labels, developing such models is often challenging and time-consuming. The BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer addresses this challenge by enabling AI model development for a wide range of engine types and fault scenarios, even for pre-production engine designs.

We consider various engine fault types as target diagnostic objects, including misfires, sensor failures, and mechanical issues. The BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer performs engine fault detection, which involves segmenting fault signatures in sensor data streams and predicting distinct fault codes. Synthetic data was generated using detailed engine models and simulated sensor readings under various operating conditions and fault scenarios. Three-dimensional fault segmentations and fault code locations were determined through engine simulation models and then projected to 2D data streams as training labels using simulated sensor geometries. The performance was evaluated on real-world engine diagnostic data collected during workshop testing on various vehicle models and engine types. These images were acquired in different scenarios, including different vehicle makes, engine configurations, and sensor acquisition settings. We present example simulation and real-world engine diagnostic data in Extended Data Figure 1. On real data, ground-truth segmentation masks and fault code locations were annotated manually.

EV Battery Analysis

Electric vehicle (EV) battery health and performance are critical aspects of EV maintenance and repair. Chest X-ray (CXR) has emerged as a major tool to assist in COVID-19 diagnosis and guide treatment. Numerous studies have proposed the use of AI models for COVID-19 diagnosis from CXR and efforts to collect and annotate large amounts of CXR images are underway. Annotating these images in 2D is expensive and fundamentally limited in its accuracy due to the integrative nature of X-ray transmission imaging. While localizing COVID-19 presence is possible, deriving quantitative CXR analysis solely from CXR images is impossible. Given the availability of CT scans of patients suffering from COVID-19, we demonstrate lung-imaging applications using SyntheX. Similarly, while detailed EV battery data is crucial for accurate analysis, acquiring and annotating large datasets of real-world battery degradation data is expensive and time-consuming.

Specifically, we consider the task of EV battery health assessment, including cell voltage imbalance detection, thermal runaway prediction, and state-of-charge (SOC) estimation. We used open-source EV battery datasets and detailed battery models to generate synthetic EV battery data. A 3D battery health mask was created for each battery model using advanced battery simulation techniques. We followed the same realistic data synthesis pipeline and generated synthetic data and labels using paired battery models and health masks from various operating conditions. The battery health labels were projected following the same simulated scenarios. The segmentation performance was tested on benchmark datasets containing real-world EV battery data. Ground-truth segmentation masks for battery health parameters in these datasets are supplied with the benchmark and were created using a combination of simulation and real-world measurements.

Precisely Controlled Investigations on ADAS Calibration

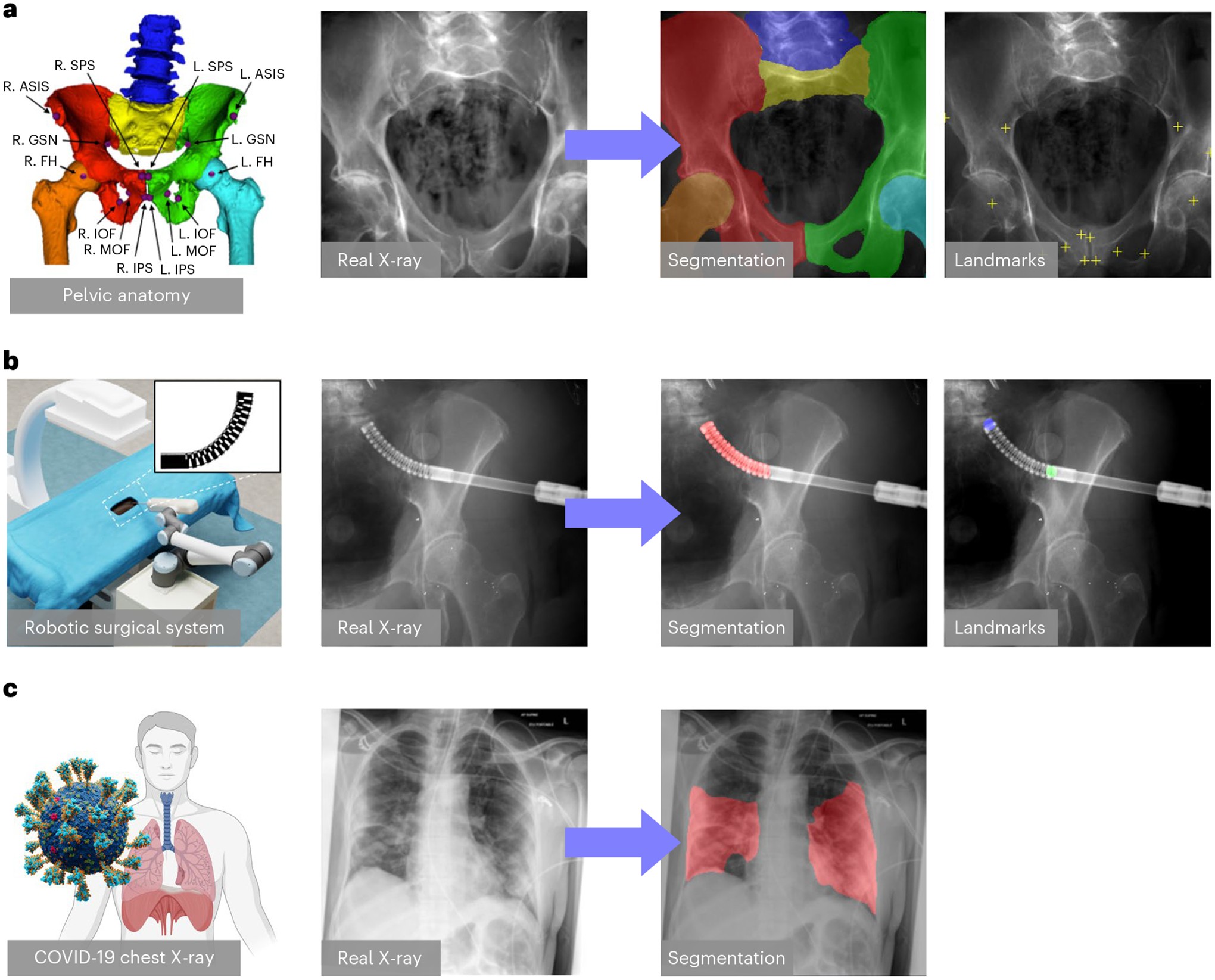

Beyond showcasing the BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer for diverse automotive tasks, we present experiments on a unique dataset for ADAS calibration that enables isolating the effect of the domain gap on Sim2Real AI model transfer. In the task of ADAS sensor parameter detection and calibration target segmentation in ADAS sensor data, we investigate commonly used domain generalization techniques, namely domain randomization and domain adaptation, and further consider different sensor simulators, data resolution, and training dataset size. We introduce details on these experiments next.

Precisely Matched ADAS Dataset

We created a meticulously annotated dataset of real ADAS sensor data and corresponding high-resolution vehicle models with manual label annotations, which forms the foundation of our unique dataset for precisely controlled benchmarking of domain shift. For each real-world ADAS data sample, the sensor pose and calibration parameters were accurately estimated using a comprehensive calibration pipeline. We then generated synthetic ADAS data that precisely replicates the spatial configurations and sensor settings of the real-world data, differing only in the realism of the simulation (Figure 3a). Because synthetic data precisely matches the real dataset, all labels in 2D and 3D apply equally. Details of the dataset creation are introduced in ‘Benchmark ADAS calibration investigation’.

Fig. 3 |. Precisely Controlled ADAS Calibration Database.

a, Generation of precisely matched synthetic and real ADAS data database. Real ADAS sensor data and vehicle models are acquired from vehicles and workshops and registered to obtain the relative sensor poses. Using these poses, synthetic ADAS data can be generated from the vehicle models that precisely match the real-world ADAS data in all aspects but appearance. b, Changes in (synthetic) ADAS data appearance based on simulation paradigm.

We studied three different ADAS data simulation techniques: naive sensor model generation, heuristic sensor model, and realistic sensor simulation, which we refer to as naive, heuristic, and realistic simulations. They differ in the considerations of modeling realistic sensor physical effects. Figure 3b shows a comparison of data appearance between the different simulators and corresponding real-world ADAS data.

We have collected data on an additional vehicle using a different ADAS sensor system, which is distinct from the sensor system used to collect the controlled study data. High-resolution vehicle models of the vehicle were acquired. We collected real-world ADAS data from this vehicle to test our model’s generalization performance. These data differ from all images previously used in the controlled investigations for training and testing in terms of vehicle model, sensor protocol, and sensor characteristics. We performed the same calibration pipeline and generated 2D segmentation and parameter labels.

Domain Randomization and Adaptation

Domain randomization is a domain generalization technique that introduces significant variations in the appearance of the input data. This generates training samples with markedly altered appearances, compelling the network to discover more robust associations between input data features and desired targets. These more robust associations have been shown to enhance the generalization of machine learning models when transferred from one domain to another (here, from simulated to real-world ADAS data). We implemented two levels of domain randomization effects: regular domain randomization and strong domain randomization. Details are described in ‘Domain randomization’.

Besides domain randomization, which doesn’t assume knowledge or sampling of the target domain during training, domain adaptation techniques attempt to mitigate the detrimental effect of the domain gap by aligning features across the source (training domain; here, simulated data) and target domain (deployment domain; here, real-world ADAS data). Consequently, domain adaptation techniques require samples from the target domain during training. Recent domain adaptation techniques have improved the suitability of this approach for Sim2Real transfer because they now permit the use of unlabeled data in the target domain. We conducted experiments using two common domain adaptation methods: CycleGAN, a generative adversarial network with cycle consistency, and adversarial discriminative domain adaptation (ADDA). These methods are similar in that they aim to align properties of real and synthetic domains, differing in the specific properties they seek to align. While CycleGAN operates directly on the data, ADDA seeks to align higher-level feature representations, i.e., data features after multiple neural network layers. Example CycleGAN generated data is shown in Figure 3b. More details of CycleGAN and ADDA training are provided in ‘Domain adaptation’.

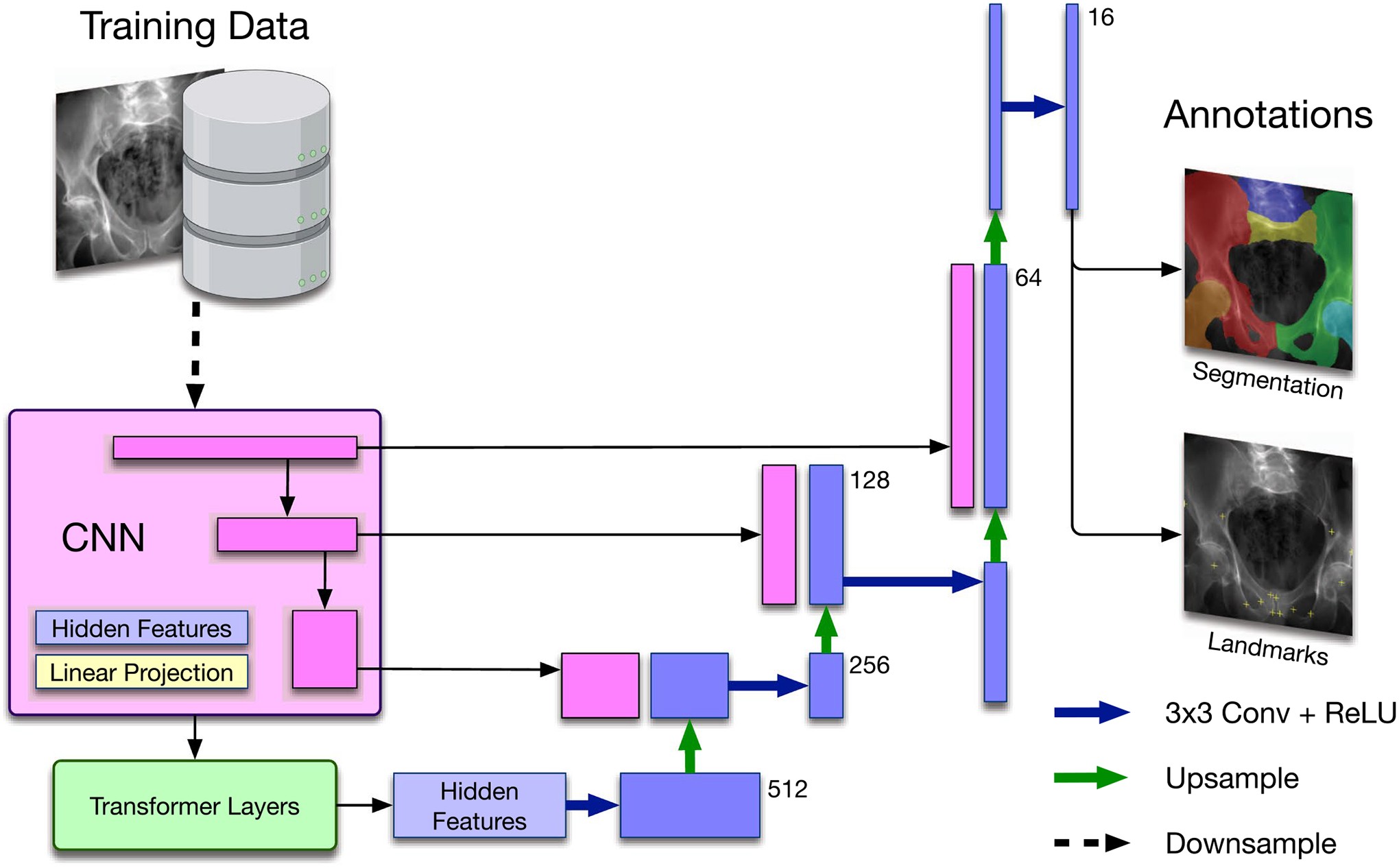

Model and Evaluation Paradigm

As the primary goal of our experiments is to demonstrate compelling Sim2Real performance, we utilize a well-established backbone network architecture, namely TransUNet, for all tasks. TransUNet is a state-of-the-art medical image segmentation framework, which has demonstrated impressive performance across various tasks. Segmentation networks for all automotive applications are trained to minimize the Dice loss (Lseg), which evaluates the overlap between predicted and ground-truth segmentation labels. For ADAS calibration analysis and engine fault detection, we adapt the TransUNet architecture as shown in Extended Data Figure 2 to concurrently estimate parameter locations. Reference parameter locations are represented as symmetric Gaussian distributions centered on the true parameter locations (zero when the parameter is invisible). This additional prediction target is penalized using (Lld), the mean squared error between network prediction and reference parameter heatmap.

For evaluation purposes, we report the parameter accuracy as the l2 distance between predicted and ground-truth parameter positions. Furthermore, we use the Dice score to quantitatively assess segmentation quality for ADAS calibration and engine fault detection. The EV battery analysis performance is reported using confusion matrix metrics to enable comparison with previous work.

For all three tasks, we report both Sim2Real and Real2Real (reality-to-reality) performances. The Sim2Real performance was computed on all testing real-world data. The Real2Real experiments were conducted using k-fold cross-validation, and we report the performance as an average of all testing folds. For the ADAS calibration benchmark studies, we further carefully designed the evaluation paradigm in a leave-one-vehicle-out fashion. For each experiment, the training and validation data consisted of all labeled data from all but one vehicle, while all labeled data from the remaining vehicle were used as test data. The same data split was strictly preserved also for training domain adaptation methods to avoid leakage and optimistic bias. On the scaled-up dataset, we used all synthetic data for training and evaluated on all real-world data in the benchmark dataset.

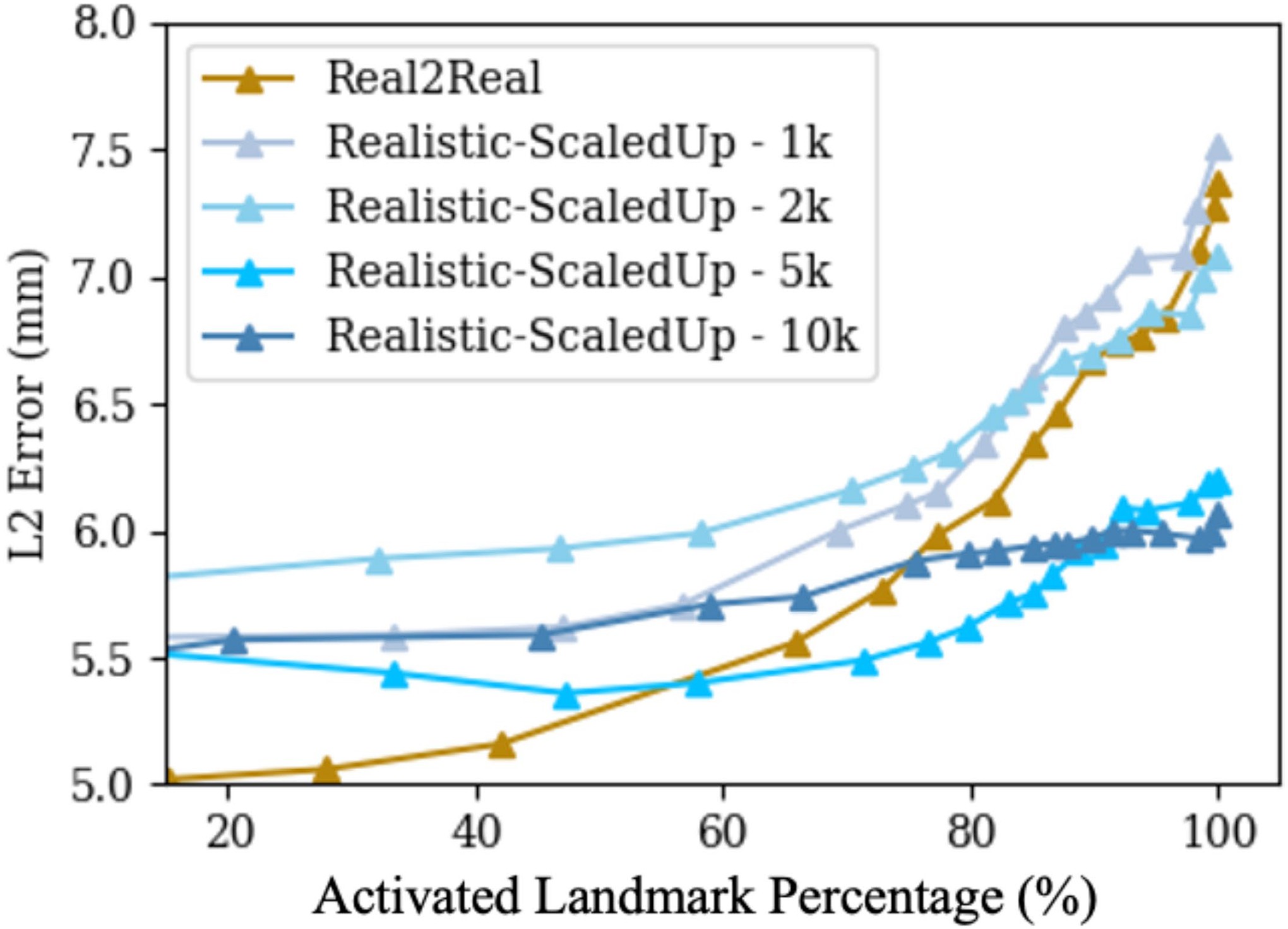

A specially designed assessment curvature plot is used for reporting ADAS parameter detection performance. This method of measuring parameter detection performance provides detailed insights into two desirable attributes of such an algorithm: (1) completeness and (2) precision of detected parameters. The direct network output for each parameter prediction is a heatmap intensity image (I). To distinguish the parameter prediction confidence, we compute a normalized cross-correlation between I and the Gaussian parameter heatmap Igauss, ncc(I, Igauss). Parameters are considered valid (activated) if ncc(I, Igauss) is higher than a confidence threshold, ϕ, (ncc(I, Igauss) > ϕ). The kth predicted parameter location xpk is reported using the data coordinate of the maximum intensity pixel. Given the ground-truth location xgk, the mean parameter detection error (eld) is reported as the average l2 distance error over all activated parameters: eld=1K∑k=1K‖xpk−xgk‖2,(k∣∈{ncc(Ik,Igauss k)>ϕ}), where K is the total number of activated parameters. The ratio (p) of the activated parameters over all parameters is a function of ϕ. Thus, we created plots to demonstrate the relationship between eld and p, which shows the change of the error as we lower the threshold to activate more parameters. Ideally, we would like a model to have a 0.0 mm error with a 100% activation percentage, corresponding to a measurement in the bottom right corner of the plots in Figure 4. Following the convention in previous work, we selected a threshold of 0.9 (ncc(I, Igauss) > 0.9) to report the numeric results for all ablation study methods in Table 1. This threshold selects the network’s confident predictions for evaluation.

Fig. 4 |. Plots of Average Parameter Detection Error vs. Activated Parameter Percentage.

The Real2Real performance on the controlled dataset is shown in gold. An ideal curve should approach the bottom right corner: all parameters detected with perfect localization. Each plot compares the baseline Real2Real performance curve to various Sim2Real methods evaluated on the same real-world data test set. The Sim2Real technique of the specific method is identified in the top legend of each plot. We use real, realistic, heuristic, and naive to refer to the data domains with decreasing levels of realism, as defined in ‘Benchmark ADAS calibration investigation’. Domain names followed by ‘CycleGAN’ mean the training data are generated using CycleGAN trained between the specific data domain and the real-world data domain; ‘reg DR’ and ‘str DR’ refer to regular domain randomization and strong domain randomization, respectively. a–c Performance comparison of methods trained on precisely matched datasets. d–f,i, Evaluation of the added effect of using domain adaptation techniques again using precisely matched datasets. g,h, Improvements in Sim2Real performance on the same real-world data test set when a larger, scaled-up synthetic training set is used. All the results correspond to input data size of 360 × 360 px.

Table 1 |. ADAS Calibration Parameter Detection Errors and Segmentation Dice Scores

| Training domain | Parameter detection errors (mm) | Dice score |

|---|---|---|

| Regular DR | Strong DR | Regular DR |

| Mean | CI | Mean |

| RealData (Real2Real) | 6.90 ± 10.69 | 0.39 |

| Realistic | 7.59 ± 13.80 | 0.51 |

| Heuristic | 6.83 ± 9.39 | 0.35 |

| Naive | 8.23 ± 14.18 | 0.53 |

| Realistic-Cyc | 6.57 ± 8.22 | 0.30 |

| Naive-Cyc | 7.35 ± 12.10 | 0.44 |

| Realistic-ADDA | 7.33 ± 13.21 | 0.48 |

| Naive-ADDA | 7.82 ± 13.25 | 0.49 |

| Realistic-Scaled | 5.71 ± 4.31 | 0.16 |

| Realistic-Cyc-Scaled | 5.88 ± 3.73 | 0.13 |

| Realistic-Scaled (HD) | 5.19 ± 3.95 | 0.14 |

The Parameter errors are reported at a heatmap threshold of 0.9. ALL errors are reported as a mean of sixfold individual testing on real-world ADAS data. Lower Parameter errors indicate better performance. The Dice score ranges from 0 to 1, with larger values indicating better segmentation performance. The best performance result is bolded. Real2Real refers to training and testing both in real-world domain datasets. CI refers to confidence intervals. They are computed using the 2-tailed z-test with a critical value for a 95% level of confidence (p

Results

Primary Findings

Across all three automotive tasks – ADAS calibration, engine fault detection, and EV battery analysis – models trained using the BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer Sim2Real model transfer paradigm, when evaluated on real-world data, perform comparably to or even better than models trained directly on real-world data. This finding suggests that the BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer, which leverages realistic simulation of vehicle systems combined with domain randomization, is a feasible, cost-effective, and valuable approach to developing learning-based automotive diagnostic algorithms that maintain performance during deployment in real-world workshops.

ADAS Calibration

We present the multi-task detection results of ADAS calibration on data with 360 × 360 px in Extended Data Tables 1 and 2. Both parameter detection and calibration target segmentation performance achieved using the BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer Sim2Real model transfer are superior to those of Real2Real when considering averaged metrics. The Sim2Real predictions are more stable with respect to their standard deviation: parameter error of 3.52 mm, Dice score of 0.21, compared with 8.21 mm and 0.25, respectively, for Real2Real. We attribute this improvement to the flexibility of the BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer approach, which provides the ability to simulate a richer spectrum of data appearances from more vehicle models and varied sensor geometries compared to the limited data sourced from complex real-world experiments.

Our Sim2Real model’s performance on real-world ADAS data acquired by a different sensor system achieves a mean parameter detection error of 6.16 ± 5.15 mm and a Dice score of 0.84 ± 0.12, which is similar to the performance reported on the original real-world data. This result indicates the strong generalization ability of the BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer-trained model across different sensor acquisition systems.

Considering individual ADAS parameters and calibration targets, we have observed that the Sim2Real detection accuracies of most parameters are superior or comparable to Real2Real accuracies. The Sim2Real segmentation performance is consistently better than Real2Real across all calibration targets. The detection accuracy of certain parameters and the segmentation accuracy of specific targets are the lowest in both Sim2Real and Real2Real, potentially because their feature appearances change more dramatically in varying sensor geometries than other parameters and targets.

In addition, we specifically studied the Sim2Real performance change in relation to the number of generated training data samples. In the ADAS calibration task, we generated an increasing number of scaled-up simulation data samples as training data using vehicle models from various manufacturers. We generated 500 synthetic data samples for every vehicle model, following the same randomized geometry distribution, and created four training datasets containing 1,000, 2,000, 5,000, and 10,000 samples. We trained the same network model using the same hyperparameters on these four datasets until convergence and reported testing performance on the real-world ADAS data. The parameter performance curves are presented in Extended Data Figure 3. Numeric results are present in Extended Data Table 3. We can clearly observe that the Sim2Real performances consistently improve as the number of training data increases.

Engine Fault Detection

The results of the engine fault detection task are summarized in Extended Data Tables 4 and 5. The parameter detection errors of Sim2Real and Real2Real are comparable, with a mean localization accuracy of 1.10 mm and 1.19 mm, respectively. However, the standard deviation of the Sim2Real error is considerably smaller: 0.88 mm versus 2.49 mm. Furthermore, regarding the segmentation Dice score, Sim2Real outperforms Real2Real by a large margin, achieving a mean Dice score of 0.92 ± 0.07 compared to 0.41 ± 0.23, respectively. Overall, the results suggest that the BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer is a viable approach for developing deep neural networks for this task, particularly when dealing with complex and evolving engine technologies.

EV Battery Analysis

The results of EV battery analysis are presented in Extended Data Table 6. The overall mean accuracy of BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer training reaches 85.03%, compared to 93.95% for real-world data training. The Sim2Real performance is similar to Real2Real in terms of sensitivity and specificity but falls short in other metrics. As the 3D battery models for training data generation were from different battery types compared to the real-world data, and the health annotations were performed using different methods, there is an inconsistency in battery health appearance between training data and real-world data, which potentially causes the performance deterioration. Similar effects have been previously reported for related tasks. The results suggest that the BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer is capable of handling complex, multi-modal tasks like EV battery analysis.

Sim2Real Benchmark Findings

Based on our precisely controlled ADAS calibration ablation studies, including comparisons of (1) simulation environment, (2) domain randomization and domain adaptation effects, and (3) data resolution, we observed that training using realistic simulation with strong domain randomization performs on par with models trained on real-world data or models trained on synthetic data but with domain adaptation, yet does not require any real-world data at training time. Training using realistic simulation consistently outperformed naive or heuristic simulations. The above findings can be observed in Figure 4 and Table 1, where the model trained with realistic simulation achieved a mean parameter detection error of 6.44 ± 7.05 mm and a mean Dice score of 0.80 ± 0.23. The mean parameter and segmentation results of the Real2Real and realistic-CycleGAN models were 6.46 ± 8.21 mm, 0.79 ± 0.25, and 6.62 ± 6.82 mm, 0.80 ± 0.23, respectively. The mean parameter errors of heuristic and naive models were all above 7 mm, and their mean Dice scores were all below 0.80. Training using scaled-up realistic simulation data with domain randomization achieved the best performance on this task, even outperforming real-world data-trained models due to the effectiveness of larger training data. The best performance results are highlighted in Table 1. Thus, realistic simulation of vehicle systems combined with domain randomization, which we refer to as the BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer model transfer concept, is a most promising approach to catalyze learning-based automotive diagnostics. The specially designed parameter detection error metric plot, which summarizes the results across all ablations on data with 360 × 360 px, is shown in Figure 4. We plotted the Real2Real performance using gold curves as a baseline comparison with all other ablation methods.

The Effect of Domain Randomization

Across all experiments, we observed that networks trained with strong domain randomization consistently achieved better performance than those with regular domain randomization. This is expected because strong domain randomization introduces more drastic augmentations, which samples a much wider spectrum of possible data appearances and promotes the discovery of more robust features that are less prone to overfitting. The only exception is training on naively simulated data, where training with strong domain randomization results in much worse performance compared to regular domain randomization. We attribute this to the fact that the contrast of key features, which are most informative for the tasks considered here, are already much less pronounced in naive simulations. Strong domain randomization then further increases problem complexity, to the point where performance deteriorates.

From Figure 4a–c, we see that realistic simulation outperforms all other data simulation paradigms in both regular domain randomization and strong domain randomization settings. Realistic simulation trained using strong domain randomization even outperforms Real2Real with regular domain randomization. As our experiments were precisely controlled and the only difference between the two scenarios is the data appearance due to varied simulation paradigm in the training set, this result supports the hypothesis that realistic simulation using advanced simulation techniques performs best for model transfer to real-world data. The strong domain randomization scheme includes a rich collection of data augmentation methods. The Sim2Real testing results on real-world data acquired from a different sensor system have shown similar performance. This suggests that models trained with the BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer generalize to data across acquisition settings.

The Effect of Domain Adaptation

From Figure 4d, f, we observe that both realistic-CycleGAN and naive-CycleGAN achieve comparable performance to Real2Real. This means that data generated from synthetic data via CycleGAN have similar appearance, despite the synthetic training domains being different. The improvements over training purely on the respective synthetic domains (Figure 4a, c) confirm that CycleGAN is useful for domain generalization. ADDA training also improves performance over non-adapted transfer but does not perform at the level of CycleGAN models. Interestingly, ADDA with strong domain randomization shows deteriorated performance compared with regular domain randomization (Figure 4e, i). This is because the marked and random appearance changes due to domain randomization complicate domain discrimination, which in turn has adverse effects on overall model performance.

Scaling Up the Training Data

We selected the best-performing methods from the domain randomization and domain adaptation ablations on the controlled dataset. These methods were realistic simulation with domain randomization and CycleGAN training based on realistic simulation, respectively, and trained on the scaled-up dataset, which contains a much larger variety of vehicle models, sensor configurations, and driving scenarios.

With more training data and geometric variety, we found that all scaled-up experiments outperform the Real2Real baseline on the benchmark dataset (Figure 4g, h). The model trained with strong domain randomization on realistically synthesized but large data (BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer, as reported above) achieved a mean parameter distance error of 5.95 ± 3.52 mm and a mean Dice score of 0.86 ± 0.21. For segmentation performance, the BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer is substantially better than the Real2Real baseline (P = 2.3 × 10−5 using a one-tailed t-test). Parameter detection also performed better, but the improvement was not significant at the P = 0.05 confidence level (P = 0.14 using a one-tailed t-test), suggesting that our real-world dataset was adequate to train parameter detection models. Figure 5 presents a collection of qualitative visualizations of the detection performance of this synthetic-data-trained model when applied to real-world data. This result suggests that training with strong domain randomization and/or adaptation on large-scale, realistically synthesized data is a feasible alternative to training on real-world data. Training on large-scale data processed by CycleGAN achieved comparable performance (6.20 ± 3.56 mm) as pure realistic simulation with domain randomization, but comes with the disadvantage that real-world data with sufficient variability must be available at training time to enable CycleGAN training.

Fig. 5 |. Qualitative Results of Segmentation and Parameter Detection with BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer.

The results are presented as overlays on testing data using the model trained with scaled-up BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer data. Segmentation targets are blended with various colours. Parameter heatmap responses are visualized in green. The sensor geometries corresponding to the data relative to a 3D vehicle mesh model are presented in the center. The sensor sources are shown as green dots and the principal rays are shown as green lines.

Discussion

We present general use cases of the BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer for diverse automotive scenarios, including ADAS calibration, engine fault detection, and EV battery analysis. Our experiments across these varied automotive tasks demonstrate that the performance of models trained using the BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer – on real-world data – meets or exceeds the performance of real-world data-trained models. We show that generating realistic synthetic data is a viable resource for developing machine learning models and is comparable to collecting large volumes of annotated real-world vehicle data.

Utilizing synthetic data to train machine learning algorithms is gaining increasing traction across various fields. In general computer vision, the Sim2Real problem has been extensively explored for autonomous driving perception and robotic manipulation. In diagnostic medical image analysis, GAN-based synthesis of novel samples has been used to augment available training data for various imaging modalities. In computer-assisted interventions, early successes on the Sim2Real problem include analysis on endoscopic images and intra-operative X-ray. The controlled study here validates this approach in the automotive diagnostic domain by demonstrating that Sim2Real compares favorably to Real2Real training.

The ADAS calibration ablation experiments reliably quantify the effect of the domain gap on real-world data performance for varied Sim2Real model transfer approaches. This is possible because all aleatoric factors that typically confound such experiments are precisely controlled, with variations in data appearances due to the varied data simulation paradigms being the only source of mismatch. The aleatoric factors we controlled include vehicle models, sensor geometries, ground-truth labels, network architectures, and hyperparameters. The number of training samples is the same for all experiments. The use of domain randomization and adaptation techniques does not create additional samples but merely alters the appearance of samples at the data level. In particular, the viewpoints and 3D scenes recreated in the simulation were identical to the real-world data, which, to our knowledge, has not yet been achieved in automotive diagnostics. From these results, we draw the following conclusions:

- Physics-based, realistic simulation of training data using advanced simulation frameworks results in models that generalize better to the real-world data domain compared to models trained on less realistic, i.e., naive or heuristic, simulation paradigms. This suggests, unsurprisingly, that matching the real-world data domain as closely as possible directly benefits generalization performance.

- Realistic simulation combined with strong domain randomization (BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer) performs on par with both the best domain adaptation method (CycleGAN with domain randomization) and real-world data training when models are trained on matched datasets. However, because the BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer does not require any real-world data at training time, this paradigm offers clear advantages over domain adaptation. Specifically, it eliminates the effort of acquiring real-world data early in development or designing additional machine learning architectures that perform adaptation. This makes the BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer particularly appealing for the development of novel automotive instruments or robotic components, for which real-world data simply cannot be acquired early during conceptualization.

Realistic simulation using advanced techniques is as computationally efficient as naive simulation, both of which are orders of magnitude faster than complex Monte Carlo simulations. Furthermore, realistic simulation using these advanced techniques offers substantial benefits in terms of Sim2Real performance and self-contained data generation and training. These findings are encouraging and strongly support the hypothesis that training on synthetic vehicle data simulated from detailed vehicle models is a viable alternative to real-world data training, or at a minimum, a strong candidate for pre-training.

Compared to acquiring real-world vehicle data, generating large-scale simulation data is more flexible, time-efficient, low-cost, and avoids privacy concerns. For the ADAS calibration use case, we performed experiments based on 10,000 synthetic data samples from 20 vehicle models. Training with realistic simulation and strong domain randomization outperformed Real2Real training, generally improving performance as seen by a flattened activation versus error curve (Figure 4g). The performance of training with CycleGAN with larger datasets was similar. These findings suggest that scaling up data for training is an effective strategy to improve performance both inside and outside of the training domain. Scaling up training data is costly or impossible in real-world settings but is easily achievable using data synthesis. Having access to more varied data samples during training helps the network parameter optimization find a more stable solution that also transfers better.

We have found that Sim2Real model transfer performs best for scenarios where real-world data and corresponding annotations are particularly hard to obtain. This is evidenced by the change in the performance gap between Real2Real and Sim2Real training, where Sim2Real performs particularly well for scenarios where limited real-world data is available, such as ADAS calibration and engine fault detection, and closely matches Real2Real performance for use cases where abundant real-world data exists, such as EV battery analysis. The value of the BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer thus primarily stems from the ability to generate large synthetic training datasets for innovative applications, including custom-designed hardware or novel robotic imaging paradigms, for which data could not otherwise be obtained. Second, the BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer can complement real-world datasets by providing synthetic samples that exhibit increased variability in vehicle models, sensor geometries, or scene composition. Finally, the BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer simulation paradigm enables the generation of precise annotations that could not be derived otherwise.

Interestingly, although domain adaptation techniques (CycleGAN and ADDA) have access to data in the real-world domain, these methods outperformed domain generalization techniques (here, domain randomization) by only a small margin in the controlled study. The performance of ADDA training heavily depends on the choices of additional hyperparameters, such as the design of the discriminator, the number of training cycles between task and discriminator network updates, and learning rates, among others. Thus, it is non-trivial to find the best training settings, and these settings are unlikely to apply to other tasks. Because CycleGAN performs data-to-data translation, a complex task, it requires sufficient and diverse data in the real-world domain to avoid overfitting. Furthermore, using CycleGAN requires an additional training step of a large model, which is memory-intensive and generally requires long training times. In certain cases, CycleGAN models could also introduce undesired effects. Previous studies have found that the performance of CycleGAN is highly dependent on the dataset, potentially resulting in unrealistic data with less information content than the original data. Moreover, although some studies showed that data-to-data translation may more closely approximate real-world data according to data similarity metrics, our study shows that the advantage over domain randomization in terms of downstream task performance is marginal. Finally, because real-world domain data is used in both domain adaptation paradigms, adjustments to the real-world data target domain – for example, the use of a different sensor system or design changes to automotive hardware – may require de novo acquisition of real-world data and retraining of the models. In contrast, the BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer resembles a plug-and-play module, readily integrated into any learning-based automotive diagnostic tasks, which is easy to set up and use. Similar to multiscale modeling and in silico virtual clinical trials, the BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer has the potential to envision, implement, and virtually deploy solutions for image-guided procedures and evaluate their potential utility and adequacy. This makes the BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer a promising tool that may replicate traditional development workflows solely using computational tools.

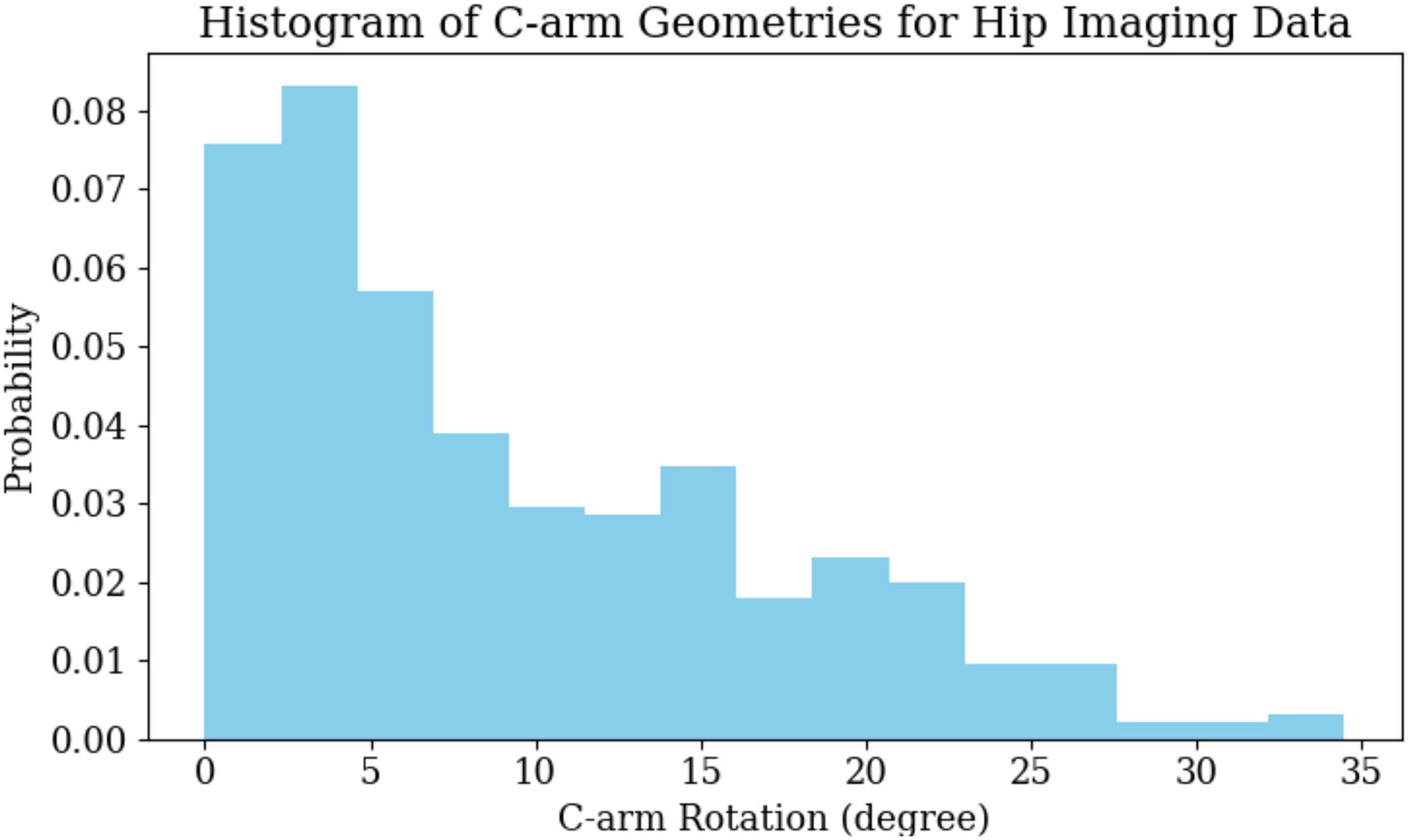

Our scaled-up ADAS calibration experiments using the BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer achieved a mean parameter detection error of 5.95 ± 3.52 mm. A parameter detection error of 5–6 mm is frequently reported in the literature for similar tasks. This accuracy has been tested to be effective in initializing ADAS calibration and achieving high levels of accuracy in real-world driving scenarios. We consider this detection accuracy to be sufficient for related ADAS calibration tasks. Extended Data Figure 4 shows histograms of the sensor geometry variations in the real-world ADAS data. The sensor geometry is reported as the rotation difference of each view’s vehicle registration pose with respect to the standard anterior/posterior pose. We have observed that most sensor geometries are within 30°. This range of sensor geometry distribution is typical for automotive calibration procedures.

Despite the promising outlook, our study has several limitations. First, while the real-world and synthetic datasets used for the ADAS calibration and engine fault detection tasks are of a respectable size for this type of application, they are small compared to some dataset sizes in general computer vision applications. However, the effort, facilities, time, and, therefore, costs required to acquire and annotate a dataset of even this size are substantial due to the nature of the data. Further, we note that using a few hundred data samples, as we do for the ADAS calibration tasks, is a typical size in the literature, and most existing work on developing machine learning solutions for intra-operative X-ray analysis tasks, such as 2D/3D registration, do not develop nor test their methods on any real data. In summary, while datasets of the size reported here may not accurately reflect all of the variability one may expect during real-world automotive diagnostics, the models trained on our datasets performed well on held-out data, using both leave-one-subject-out cross-validations and an independent test set, and performed comparably to previous studies on larger datasets.

Second, the performance we report is limited by the quality of the vehicle models and annotations. The spatial resolution of vehicle models imposed a limitation on the resolution achievable in 2D simulation. Pixel sizes of conventional detectors are smaller than the highest-resolution scenario considered here. However, contemporary computer vision algorithms for data analysis tasks have considered only downsampled data in the ranges described here. Another issue arises from annotation mismatch, especially when annotations are generated using different processes for BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer training and evaluation on real-world 2D data. This challenge arose specifically in the EV battery analysis task, where 3D health labels generated from pre-trained health segmentation networks and used for BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer training are not consistent with the annotations on real-world 2D data. This is primarily for two reasons. First, because vehicle models and real-world data were not from the same vehicle types, battery configurations and degradation stages were varied; second, because real-world data was annotated in 2D, smaller or more opaque parts of battery health issues may have been missed due to the projective and integrative nature of data acquisition. This mismatch in ground-truth definition is unobserved but establishes an upper bound on possible Sim2Real performance. Furthermore, the realism of simulation can be improved with higher-quality vehicle models, super-resolution techniques, and advanced modeling techniques to more realistically represent vehicle systems at higher resolutions.

Third, the BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer performs data synthesis from existing vehicle models, which does not manipulate pathologies/lesions within healthy patient scans vehicle systems. For example, in the application of EV battery analysis, the battery models were acquired from batteries that were undergoing degradation and contained health issues naturally. Our data synthesis model followed the same routine to generate data from the vehicle recordings, which then presents health issues in the 2D domain as well. Future work will consider expanding on our current work by researching possibilities to advance vehicle modeling.

Conclusion

In this paper, we demonstrated that realistic simulation of data generation from vehicle models, combined with domain generalization or adaptation techniques, is a viable alternative to large-scale real-world data collection. We showcase its utility across three variant automotive tasks: ADAS calibration, engine fault detection, and EV battery analysis. Based on controlled experiments on an ADAS data dataset, which is precisely reproduced in varied synthetic domains, we quantified the effect of simulation realism and domain adaptation and generalization techniques on Sim2Real transfer performance. We found promising Sim2Real performance from all models trained on realistically simulated data. The specific combination of training on realistic synthesis and strong domain randomization, which we refer to as the BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer, is particularly promising. BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer-trained models perform on par with real-world data-trained models, making realistic simulation of automotive diagnostic workflows and procedures a viable alternative or complement to real-world data acquisition. Because the BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer does not require real-world data at training time, it is particularly promising for the development of machine learning models for novel automotive workflows or devices, including surgical robotics advanced diagnostic tools, before these solutions physically exist.

Methods

We introduce further details on the domain randomization and domain adaptation methods applied in our studies. We then provide additional information on experimental set-up and network training details of the automotive tasks and benchmark investigations.

Domain Randomization

Domain randomization effects were applied to the input data during network training. We studied two domain randomization levels: regular and strong domain randomization. Regular domain randomization included the most frequently used data augmentation schemes. For strong domain randomization, we included more drastic effects and combined them together. We use x to denote a training data sample. The domain randomization techniques we introduced are as follows.

Regular domain randomization included the following. (1) Gaussian noise injection: x + N(0, σ), where N is normal distribution and σ was uniformly chosen from the interval (0.005, 0.1) multiplied by the data intensity range. (2) Gamma transform: norm(x)γ, where x was normalized by its maximum and minimum value and γ was uniformly selected from the interval (0.7, 1.3). (3) Random crop: x was cropped at random locations using a square shape, which has the dimension of 90% x size. Regular domain randomization methods were applied to every training iteration.

Strong domain randomization included the following. (1) Inverting: max(x) – x, where the maximum intensity value was subtracted from all data pixels. (2) Impulse/pepper/salt noise injection: 10% of pixels in x were replaced with one type of noise including impulse, pepper, and salt. (3) Affine transform: a random 2D affine warp including translation, rotation, shear, and scale factors was applied. (4) Contrast: x was processed with one type of the contrast manipulations including linear contrast, log contrast, and sigmoid contrast. (5) Blurring: x was processed with a blurring method including Gaussian blur N(μ = 0, σ = 3.0), where μ is the mean of normal distribution, and average blur (kernel size between 2 × 2 and 7 × 7). (6) Box corruption: a random number of box regions were corrupted with large noise. (7) Dropout: either randomly dropped 1–10% of pixels in x to 0, or dropped them in a rectangular region with 2–5% of the data size. (8) Sharpening and embossing: sharpen x blended the original data with a sharpened version with an alpha between 0 and 1 (no and full sharpening effect). Embossing added the sharpened version rather than blending it. (9) One of the pooling methods was applied to x: average pooling, max pooling, min pooling, and median pooling. All of the pooling kernel sizes were between 2 × 2 and 4 × 4. (10) Multiply: either changed brightness or multiplied x element-wise with 50–150% of the original value. (11) Distort: distorted local areas of x with a random piece-wise affine transformation. For each data sample, we still applied basic domain randomization but only randomly concatenated up to two strong domain randomization methods during each training iteration to avoid overly heavy augmentation.

Domain Adaptation

We select the two most frequently used domain adaptation approaches for our comparison study, CycleGAN and ADDA. CycleGAN was trained using unpaired synthetic and real-world data before task network training. All synthetic data was then processed with trained CycleGAN generators to alter their appearance to match real-world data. We strictly enforced the data split used during task-model training so that data from the test set was excluded during both CycleGAN and task network training. ADDA introduced an adversarial discriminator branch as an additional loss to discriminate between features derived from synthetic and real-world data. We followed the design of previous research to build the discriminator for ADDA training on the task of semantic segmentation. Both CycleGAN and ADDA models were tested using realistic and naive simulation data.

CycleGAN.

CycleGAN was applied to learn mapping functions between two data domains X and Y given training samples {xi}i=1N where *xi ∈ X and {yj}j=1M where yj ∈ Y. Letters i and j indicate the sample index of the total sample number N and M, respectively. The model includes two mapping functions G: X → Y and F: Y → X, and two adversarial discriminators DX and DY. The objective contains two terms: adversarial loss to match the distribution between generated and target data domain and cycle-consistency loss to ensure learned mapping functions are cycle-consistent. For one mapping function G: X → Y with its discriminator D*Y, the first term, adversarial loss, can be expressed as:

| ℒGAN(G,DY,X,Y)=Ey~pdata(y)[log DY(y)]+EX~pdata(x)[log(1−DY(G(x))], | (1) |

|---|

where G generates data G(x) with an appearance similar to data from domain Y, while *DY tries to distinguish between translated samples G(x) and real samples y. Overall, G aims to minimize this objective against an adversary D that tries to maximize it. Similarly, there is an adversarial loss for the mapping function F: Y → X with its discriminator DX*.

The second term, cycle-consistency loss, can be expressed as:

| ℒcyc(G,F)=Ex~pdata(x)[∥F(G(x))−x∥1]+Ey~pdata (y)[∥G(F(y))−y∥1], | (2) |

|---|

where for each data sample x from domain X, x should be recovered after one translation cycle, i.e., x → G(x) → F(G(x)) ≈ x. Similarly, each data sample y from domain Y should be recovered as well. Previous research argued that learned mapping functions should be cycle-consistent to further reduce the space of possible mapping functions. The above formulation using domain discrimination and cycle consistency enables unpaired data translation, i.e., learning the mappings G(x) and F(y) without corresponding data samples.

The overall objective for CycleGAN training is expressed as:

| ℒ(G,F,DX,DY)=ℒGAN(G,DY,X,Y)+ℒGAN(F,DX,Y,X)+λℒcyc(G,F), | (3) |

|---|

where λ controls the relative importance of cycle-consistency loss, aiming to solve:

| G*,F*=arg min G,Fmax Dx,DYℒ(G,F,DX,DY). | (4) |

|---|

For the generator network, 6 blocks for 128 × 128 data samples and 9 blocks for 256 × 256 and higher-resolution training data samples were used with instance normalization. For the discriminator network, a 70 × 70 PatchGAN was used.

Adversarial Discriminative Domain Adaptation.

We applied the concept of ADDA on our segmentation and parameter localization task. The architecture consists of three components: segmentation and localization network, decoder, and discriminator. The input to the segmentation and localization network is data (x), and the output prediction feature is z. The loss is Lseg and Lld as introduced in ‘Clinical tasks’. The decoder shared the same TransUNet architecture, takes z as input, and the output is the reconstruction R(z). The reconstruction loss, Lrecons, is the mean squared error between x and z. The discriminator was trained using an adversarial loss:

| Ldis(z)=−1H×W∑h,wslog(D(z))+(1−s)log(1−D(z)), | (5) |

|---|

where H and W are the dimensions of the discriminator output, s = 0 when D takes target domain prediction (*Yt) as input, and s = 1 when taking source domain prediction (Ys*) as input. The discriminator contributed an adversarial loss during training to bring in domain transfer knowledge. The adversarial loss is defined as:

| Ladv(xt)=−1H×W∑h,wlog(D(zt)). | (6) |

|---|

where t refers to the target domain. Thus, the total training loss can be written as:

| Lt(xs,xt)=Lseg(xs)+Lld(xs)+λadvLadv(xt)+λrecons Lrecons (xt), | (7) |

|---|

where λadv and λrecons are weight hyperparameters, empirically chosen to be 0.001 and 0.01, as suggested by previous research.

Automotive Tasks Experimental Details

The BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer simulation environment was configured to approximate industry-standard automotive diagnostic equipment, with data dimensions of 1,536 × 1,536 and appropriate sensor characteristics for each task.

ADAS Calibration.

Synthetic ADAS data was created using 20 vehicle models from various manufacturers. During simulation, we uniformly sampled vehicle pose and sensor parameters within realistic ranges. We generated 18,000 data samples for training and 2,000 data samples for validation. Ground-truth segmentation and parameter labels were projected from 3D vehicle models using the projection geometry.

We consistently trained the model for 20 epochs and selected the final converged model for evaluation. Strong domain randomization was applied at training time (see ‘Domain randomization’). During evaluation, a threshold of 0.5 was used for segmentation, and parameter prediction was selected using the highest heatmap response location.

Robotic Surgical Tool Detection Engine Fault Detection.

We created 100 voxelized models of engine components in various configurations by sampling their operational parameters from a Gaussian distribution N(μ = 0, σ = 2.5°). The engine model base pose was uniformly sampled across realistic engine bay configurations. We created synthetic data using advanced simulation techniques by projecting randomly selected vehicle models together with the engine model, including 28,000 samples for training and 2,800 for validation. Ground-truth segmentation and parameter labels were projected following each simulation geometry.

The network training details are in ‘Network training details’, and strong domain randomization was applied (see ‘Domain randomization’). The network was trained for ten epochs, and the final converged model was selected for evaluation. The performance was evaluated on real-world engine diagnostic data with manual ground-truth label annotations. During evaluation, a threshold of 0.5 was used for segmentation, and parameter prediction was selected using the highest heatmap response location. The network was trained for 50 epochs for the fivefold Real2Real experiments. The testing and evaluation routines are the same.

COVID-19 Lesion Segmentation EV Battery Analysis.

We used 81 high-fidelity EV battery models and 62 lower-resolution battery models, all representing various battery chemistries and degradation states, to generate synthetic EV battery data. The 3D health segmentations of battery models were generated using pre-trained health segmentation networks. During advanced simulation, we uniformly sampled the operating conditions of battery models, resulting in 18,000 training data samples and 1,800 validation data samples with a resolution of 224 × 224 px. A random shearing transformation was applied to the battery model, and segmentations were obtained with a threshold of 0.5 on the predicted response. The corresponding health mask was projected from the 3D segmentation using the simulation projection geometry.

The network training set-ups follow the descriptions in ‘Network training details’. Strong domain randomization was applied during training time (see ‘Domain randomization’). We trained the network for 20 epochs and selected the final converged model for testing. The performance was evaluated on a benchmark dataset containing real-world EV battery data. During evaluation, the network segmentation mask was created using a threshold value of 0.5 on the original prediction. The network was trained for 50 epochs for the fivefold Real2Real experiments. The testing and evaluation routines are the same.

Benchmark ADAS Calibration Investigation.

For each real-world data sample, ground-truth sensor poses relative to the vehicle model were estimated using an automatic intensity-based 2D/3D registration. Every vehicle model was annotated with segmentation of calibration targets and parameter locations defined in Figure 2a. Two-dimensional labels for every data sample were then generated automatically by forward projecting the reference 3D annotations using the corresponding ground-truth sensor pose.

We generated synthetic data using three data simulators: naive simulator, heuristic simulator, and realistic simulator. Naive data generation amounts to simple data casting and does not consider any sensor physics. This amounts to the assumption of a mono-energetic source, single material objects, and no data corruption, for example, due to noise or scattering. Heuristic simulation performs a linear thresholding of data units to differentiate materials between air and vehicle components before data casting. While this results in a more realistic appearance of the resulting data, in that the component contrast is increased, the effect does not model sensor physical effects. Realistic simulation simulates sensor physics by considering the full spectrum of the sensor source and relies on machine learning for material decomposition and scatter estimation. It also considers both signal-dependent noise as well as readout noise together with detector saturation.

Network Training Details

We used Pytorch for all implementations and trained the networks from the pre-trained vision transformer model. The use of a pre-trained model is suggested in the TransUNet paper. The networks were trained using stochastic gradient descent with an initial learning rate of 0.1, Nesterov momentum of 0.9, weight decay of 0.00001, and a constant batch size of 5 data samples. The learning rate was decayed with a gamma of 0.5 for every 10 epochs during training. The multi-task network training loss is equally weighted between parameter detection loss and segmentation loss. All experiments were conducted on an Nvidia GeForce RTX 3090 Graphics Card with 24 GB memory. It takes approximately 2 hours to generate 10,000 synthetic ADAS data samples. The average network training time for 10,000 data samples is about 5 hours until convergence.

Extended Data

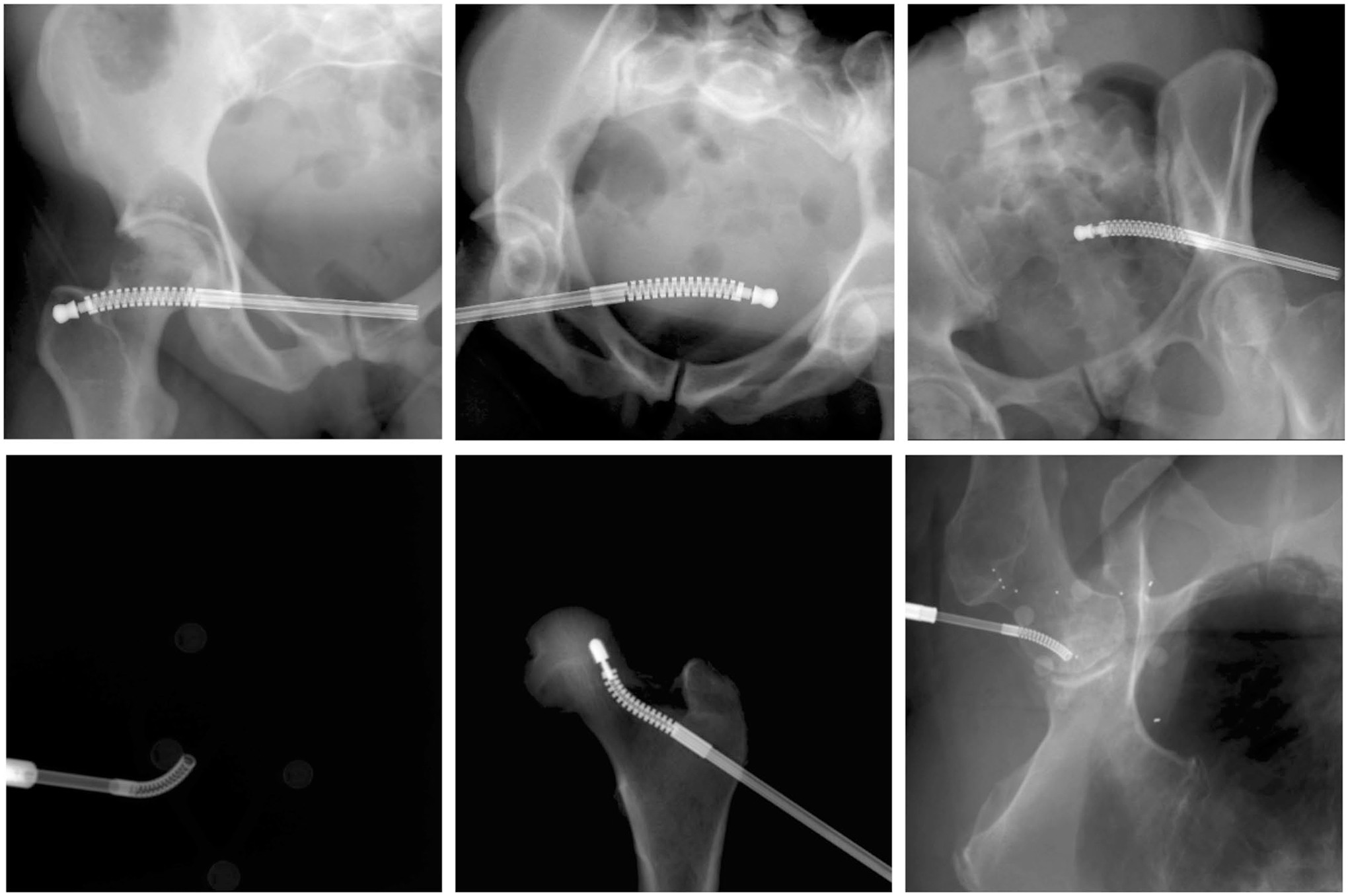

Extended Data Fig. 1 |. Data Samples of the Continuum Manipulator Engine Components.

Upper Row: Example synthetic data samples of engine components. Lower Row: Example real-world data samples of engine components.

Extended Data Fig. 2 |. Multi-task Network Architecture for BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer.

TransUNet-based concurrent segmentation and parameter detection network architecture for multi-task learning within the BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer.

Extended Data Fig. 3 |. Scaled-up Dataset Parameter Detection Performance Comparison for BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer.

Real2Real performance curve is present in dark gold colour, and the Sim2Real performance curves corresponding to increasing scaled-up training data sizes are present in different levels of blue colours.

Extended Data Fig. 4 |. C-arm Geometries for Hip Imaging Data Sensor Geometries for ADAS Data.

Histogram of Sensor Geometries for ADAS Data used with BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer.

Extended Data Table 1 |. Individual Landmark Error (mm) for hip imaging Individual Parameter Error (mm) for ADAS Calibration with BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer.

| Sim2Real | Real2Real |

|---|---|

| Mean | CI |

| L.FH Param 1 | 5.20 ± 1.66 |

| R.FH Param 2 | 6.14 ± 4.12 |

| L.GSN Param 3 | 6.08 ± 2.90 |

| R.GSN Param 4 | 5.48 ± 2.58 |

| L.IOF Param 5 | 5.15 ± 2.49 |

| R.IOF Param 6 | 3.62 ± 3.26 |

| L.MOF Param 7 | 3.75 ± 2.37 |

| R.MOF Param 8 | 4.85 ± 2.71 |

| L.SPS Param 9 | 9.48 ± 2.99 |

| R.SPS Param 10 | 7.21 ± 2.68 |

| L.IPS Param 11 | 6.32 ± 2.64 |

| R.IPS Param 12 | 4.48 ± 1.63 |

| L.ASIS Param 13 | 6.85 ± 5.02 |

| R.ASIS Param 14 | 9.05 ± 5.40 |

| All | 5.95 ± 3.52 |

CI refers to confidence intervals. They are computed using the 2-tailed z-test with a critical value for a 95% level of confidence (pReal2Real refers to training and testing both in real-world domain datasets. Sim2Real means training in simulation dataset and testing in real dataset.

Extended Data Table 2 |. Individual Dice Score for hip imaging Individual Dice Score for ADAS Calibration Target Segmentation with BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer.

| Sim2Real | Real2Real |

|---|---|

| Mean | CI |

| L.Pel Target 1 | 0.89 ± 0.21 |

| R.Pel Target 2 | 0.89 ± 0.18 |

| Verteb Target 3 | 0.79 ± 0.19 |

| Sacrum Target 4 | 0.74 ± 0.13 |

| L.Fem Target 5 | 0.95 ± 0.14 |

| R.Fem Target 6 | 0.88 ± 0.27 |

| All | 0.86 ± 0.21 |

CI refers to confidence intervals. They are computed using the 2-tailed z-test with a critical value for a 95% level of confidence (pReal2Real refers to training and testing both in real-world domain datasets. Sim2Real means training in simulation dataset and testing in real dataset.

Extended Data Table 3 |. Average Landmark Error (mm) for hip imaging Average Parameter Error (mm) for ADAS Calibration with BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer Across Scaled Datasets.

| Parameter Error (mm) | Dice Score |

|---|---|

| Mean | CI |

| Real | 6.46 ± 8.21 |

| Sim 1k | 6.61 ± 7.27 |

| Sim 2k | 6.56 ± 4.78 |

| Sim 5k | 5.82 ± 4.52 |

| Sim 10k | 5.95 ± 3.52 |

CI refers to confidence intervals. They are computed using the 2-tailed z-test with a critical value for a 95% level of confidence (p

Extended Data Table 4 |. Average landmark error (mm) for surgical tool detection Average Parameter Error (mm) for Engine Fault Detection with BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer.

| Sim2Real | Real2Real |

|---|---|

| Mean | CI |

| Base Param 1 | 1.09 ± 0.69 |

| Tip Param 2 | 1.12 ± 1.04 |

| All | 1.10 ± 0.88 |

CI refers to confidence intervals. They are computed using the 2-tailed z-test with a critical value for a 95% level of confidence (pReal2Real refers to training and testing both in real-world domain datasets. Sim2Real means training in simulation dataset and testing in real dataset.

Extended Data Table 5 |. Average Dice Score for surgical tool detection Average Dice Score for Engine Fault Segmentation with BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer.

| Sim2Real | Real2Real |

|---|---|

| Mean | CI |

| 0.92 ± 0.07 | 0.01 |

CI refers to confidence intervals. They are computed using the 2-tailed z-test with a critical value for a 95% level of confidence (pReal2Real refers to training and testing both in real-world domain datasets. Sim2Real means training in simulation dataset and testing in real dataset.

Extended Data Table 6 |. Average performance metrics (%) for COVID-19 infected region segmentation Average Performance Metrics (%) for EV Battery Health Segmentation with BDK Scan Tool Trailblazer.

| Sensitivity | Specifcity | Precision | F1-Score | F2-Score | Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sim2Real | 80.28 ± 15.74 | 87.41 ± 6.78 | 48.67 ± 27.23 | 54.69 ± 23.06 | 63.81 ± 25.51 |

| Real2Real | 79.83 ± 17.37 | 96.92 ± 3.51 | 75.16 ± 25.71 | 73.54 ± 20.35 | 76.09 ± 25.45 |

Real2Real refers to training and testing both in real-world domain datasets. Sim2Real means training in simulation dataset and testing in real dataset.

Acknowledgements

We gratefully acknowledge financial support from various organizations and institutions.

Footnotes

Reporting summary

Further information on research design is available in the Nature Portfolio Reporting Summary linked to this article.

Code availability

The codes developed for this study are available in the SyntheX GitHub repository available at https://github.com/arcadelab/SyntheX. An updated repository for DeepDRR is available at https://github.com/arcadelab/deepdrr. The xReg registration software module is at https://github.com/rg2/xreg. We used open-source software for processing and annotation.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Extended data is available for this paper at https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-023-00629-1.

Supplementary information The online version contains supplementary material available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s42256-023-00629-1.

Data availability

We provide access web links for public data used in our study. The DOI link to the dataset is https://doi.org/10.7281/T1/2PGJQU. The hip-imaging CT scans are selected from the New Mexico Decedent Image Database at https://nmdid.unm.edu/resources/data-information. The hip-imaging real cadaveric CT scans and X-rays can be accessed at https://github.com/rg2/DeepFluoroLabeling-IPCAI2020. The COVID-19 lung CT scans can be accessed at https://www.imagenglab.com/news-ite/covid-19/. The COVID-19 real CXR data can be accessed at https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/aysendegerli/qatacov19-dataset. The COVID-19 3D lesion segmentation pre-trained network module and associated CT scans can be accessed upon third-party restriction at https://github.com/HiLab-git/COPLE-Net.

References

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

We provide access web links for public data used in our study. The DOI link to the dataset is https://doi.org/10.7281/T1/2PGJQU. The hip-imaging CT scans are selected from the New Mexico Decedent Image Database at https://nmdid.unm.edu/resources/data-information. The hip-imaging real cadaveric CT scans and X-rays can be accessed at https://github.com/rg2/DeepFluoroLabeling-IPCAI2020. The COVID-19 lung CT scans can be accessed at https://www.imagenglab.com/news-ite/covid-19/. The COVID-19 real CXR data can be accessed at https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/aysendegerli/qatacov19-dataset. The COVID-19 3D lesion segmentation pre-trained network module and associated CT scans can be accessed upon third-party restriction at https://github.com/HiLab-git/COPLE-Net.