TrickBot, also known as Trickster or The Trick, is a notorious Trojan that has been plaguing Windows systems since 2016. Initially designed as a banking Trojan, this sophisticated malware, developed by the Russian-based Wizard Spider group, has evolved into a modular threat capable of a wide range of malicious activities. Cybersecurity researchers and antivirus companies consistently ranked TrickBot among the most active Trojans, often placing it in the top 10 most prevalent malware. Its ability to steal banking credentials is just the tip of the iceberg; TrickBot’s modular nature, built using C++, allows attackers to deploy specific modules for tailored attacks. Experts at Mitre.org have documented at least 29 distinct techniques employed by TrickBot, highlighting its versatility and adaptability.

Understanding how to detect and remove threats like TrickBot is crucial in today’s digital landscape. One powerful tool in the cybersecurity arsenal is the Farbar Recovery Scan Tool (FRST). This guide will explain how to use Farbar Recovery Scan Tool to identify and address potential TrickBot infections, drawing from the history and characteristics of this malware to inform effective remediation strategies.

Understanding the TrickBot Threat: A Timeline of Evolution

To effectively combat TrickBot, it’s important to understand its history and how it has evolved over time. Here’s a look at key milestones in TrickBot’s development:

September 2016: The Genesis of TrickBot

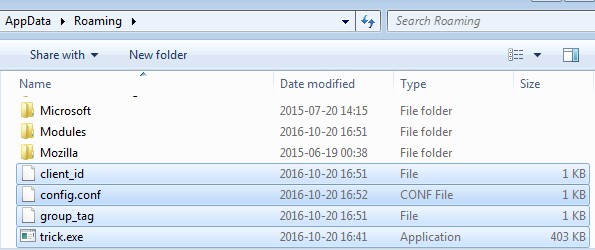

Security researchers at Malwarebytes Labs discovered a new bot resembling the Dyre (Dyreza) Trojan. Jérôme Segura, the researcher who identified it, named it TrickBot based on text found within its code. TrickBot initially spread through malvertising, malicious ads containing the Rig Exploit Kit (EK). This malware typically used JavaScript code to download TrickBot onto the computers of users who visited infected websites. Upon infection, TrickBot would copy itself to the /APPDATA/ folder, naming itself “trick.exe.” A “Modules” folder, along with configuration files, was downloaded from the Command and Control (CnC) server.

Early versions of TrickBot featured modules like injectDll32 and systeminfo32. injectDll32 was a banking module designed to infect browsers and steal user credentials, while systeminfo32 collected system information and sent it to the CnC server. To ensure persistence, TrickBot added itself to the Windows Task Scheduler, executing its code at regular intervals daily.

The similarities in code and operation to Dyre were striking. Both Trojans even used Cutwail as a spambot for distributing spam emails. IBM researcher Limor Kessem suggested a connection between the creators of TrickBot and Dyre, suspecting that the Dyre team was involved in TrickBot’s development and operations. Dyre, a prominent Trojan in 2015, saw its operations disrupted after a raid by the Federalnaya Sluzhba Bezopasnosti (FSB) on the Moscow-based 25th Floor company in November 2015. The leader of Dyre, believed to also be behind Dridex, remained unknown, but many cybersecurity experts suspected Evgeniy Bogachev, an FBI Most Wanted cybercriminal linked to the Business Club, Gameover Zeus malware, and Cryptolocker ransomware. Dyre’s emergence shortly after the takedown of Gameover Zeus in June 2014 further fueled these suspicions.

December 2016: Expanding Data Theft Capabilities

TrickBot’s capabilities expanded with a new module, mailsearcher32. This module scanned computer files, comparing extensions against a configuration file (mailsearcher32_configs) and exfiltrating found email data to the CnC server. Another module, importDll32, emerged, targeting browser data such as cookies, local databases (Flash SharedObjects, HTML5 local storage, SQLite), and website visit counts. It also included browser fingerprinting capabilities, creating a hidden desktop and opening a browser to collect configurations without user knowledge.

July 2017: EternalBlue Exploitation Testing

By mid-2017, TrickBot became a highly active banking Trojan, according to IBM X-Force Research. After initially targeting European, Australian, and US financial institutions, it expanded to Latin America, including Argentina, Chile, Colombia, and Peru, utilizing the Necrus botnet for spam email distribution. A new module, outlookDll32, was added to steal email data from Outlook. Beyond malvertising, TrickBot’s creators experimented with fake websites as malware distribution channels, as noted by Kessem from IBM.

Flashpoint researchers revealed TrickBot’s incorporation of a worm-like module, wormDll32, leveraging the EternalBlue exploit. This allowed TrickBot to spread more effectively within targeted financial institutions’ networks. EternalBlue (MS17-010) exploited a vulnerability in Windows’ Server Message Block (SMB) protocol, enabling TrickBot to identify network computers. Unlike the aggressive spreading of WannaCry and NotPetya ransomware, TrickBot appeared to be testing EternalBlue’s utility for stealthy data theft rather than causing widespread disruption.

November 2017: Account Takeover Tactics

A new module, bcClientDllTest, introduced account takeover (ATO) capabilities. Vitali Kremez of Flashpoint reported that TrickBot downloaded a SOCK5 proxy module from its server, using the victim’s IP as a proxy to test online accounts. TrickBot attempted username-password combinations, simulating logins from mobile devices to bypass traditional anti-fraud detection focused on website logins.

March 2018: Screenlocker Experiments

Researchers discovered the tabDll32 or spreader_x86.dll module, containing SsExecutor_x86.exe and screenLocker_x86.dll. Ssexecutor enhanced stealth by modifying Windows registry settings, while Screenlocker locked the victim’s computer screen. This screen-locking function seemed to deviate from TrickBot’s primary goal of banking data theft. Speculation arose that TrickBot operators recognized that corporate network users might not frequently engage in online banking. Fortinet researchers clarified in April 2018 that the screenlocker feature wasn’t for ransomware purposes but to force users to re-enter passwords upon login. TrickBot then used Mimikatz, a tool for credential theft from memory, to capture these credentials.

August 2018: Stealth and Evasion Techniques

A TrickBot variant emerged with stealth techniques to inject malware code into Windows memory, replacing legitimate executable sections (Hollow Process Injection). This allowed malware code to run directly by the kernel without additional applications. This new TrickBot also aimed to evade antivirus analysis and disable Windows security features like Windows Defender, similar to the Flokibot banking Trojan.

One notable tactic was the “zoom in” technique. After a macro-laden MS Word file was opened and macros enabled, malicious code wouldn’t immediately activate. Instead, it triggered when the user used the zoom in/out feature (via the slider at the document’s bottom right). The macro executed PowerShell code to download and run TrickBot.

To further evade security systems, TrickBot employed a 30-second “sleep” command (Sleep(30)), followed by repeated calls to CreateWindowEx and InSendMessage (for creating and sending messages to other processes), which were never actually executed. TrickBot then slept again for 11 seconds using Sleep(3) (3 microseconds sleep) called 3890 times. Cyberbit.com researcher Hod Gavriel interpreted these techniques as attempts to evade antivirus analysis. To operate undetected, TrickBot disabled and removed Windows Defender. Like previous versions, TrickBot copied itself to /AppData/Roaming/msnet and downloaded modules from its CnC server, this time using the executable name 1c9_patched.exe.

November 2018: Network Invasion and POS Targeting

This TrickBot edition introduced a module to steal passwords from Microsoft Outlook, Filezilla, WinSCP, Chrome, Firefox, Microsoft IE, and Microsoft Edge, named pwgrab32. It did not, however, target passwords from dedicated password management applications.

New modules shareDll32 and wormDll32 were added to spread TrickBot across networks. shareDll32 downloaded TrickBot from the CnC server, while wormDll32 identified servers and domain controllers for network-wide propagation. The networkDll32 module scanned networks and stole valuable information. TrickBot implemented auto-start services with names like “Service Techno,” “Service_Techno2,” “Technics-service2,” “Technoservices,” “dvanced-Technic-Service,” and “ServiceTechno5” to ensure persistence.

Another new module, psfin32, checked for point-of-sale (POS) software or connections to POS machines on infected computers.

psfin32 identified POS services using LDAP (Lightweight Directory Access Protocol) queries, a standard protocol for locating files or devices on a network, accessing Active Directory Services (ADS) to gather information about network objects. TrickBot sent collected POS information to its CnC server. While no immediate actions based on this POS data were observed, researchers speculated that TrickBot’s developers were preparing to target POS systems, potentially to capitalize on increased transaction volumes during the holiday season.

January 2019: Ransomware Partnership

Researchers from FireEye and CrowdStrike reported TrickBot’s involvement in spreading Ryuk ransomware, suggesting a business agreement between the two cybercriminal groups. TrickBot was likely rented by Ryuk operators to gain initial access to compromised networks. TrickBot, delivered via macro-infected MS Word attachments, established remote access, then deployed Ryuk ransomware within the infected networks.

February 2019: Remote Application Credentials Theft

TrickBot’s developers continued to enhance its capabilities. A new version of pwgrab32 was released, adding the ability to steal credentials from remote application platforms like Virtual Network Computing (VNC), PuTTY, and Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP). Successful credential theft from these applications allowed TrickBot operators to remotely control compromised computers.

April 2019: Triple Threat Campaigns

Building on the Ryuk ransomware partnership, TrickBot became part of a “Triple Threat” attack chain alongside Emotet and Ryuk. This combination saw Emotet initially infect systems, followed by TrickBot, and ultimately Ryuk ransomware to encrypt victim’s data.

According to Cybereason.com, Emotet infections began with macro-laden MS Word email attachments, downloading Emotet from various domains. After information gathering, Emotet downloaded TrickBot. TrickBot created folders in AppDataRoaming with executables, settings.ini, and a “Data” folder for its modules. After memory injection and disabling Windows Defender, TrickBot loaded modules into legitimate Windows processes like Service Host Process (svchost). TrickBot then assessed if the victim was in a Ryuk-targeted industry. If so, it moved to the domain controller, copying tools like AdFind.exe and 7-Zip archiver. The final stage involved downloading Ryuk ransomware, with Ryuk.exe acting as the dropper.

July 2019: Web Injection Techniques

TrickBot adopted web injection code from BokBot (IcedID). IBM X-Force researchers observed BokBot redirecting victims to fake banking sites or manipulating browsers to display fake content on legitimate banking websites. Infections started with macro-embedded MS Word files downloading the Ursnif Trojan, which then downloaded a TrickBot variant with BokBot proxy modules, named shadnewDll64 and configuration folder shadnewDll64_configs, found in AppData/Roaming/mslibrary/data. This new module could intercept and modify web traffic, using man-in-the-browser techniques to inject fake data into traffic received by the victim’s browser, acting as a local proxy between the browser and online banking sites. Victims were presented with fake login pages or manipulated legitimate banking pages.

August 2019: Fileless Operation

IBM X-Force researchers identified a significant change in TrickBot’s operation, specifically targeting 64-bit Windows 10 systems. TrickBot became fileless, no longer storing module and configuration files on disk. It checked system architecture and executed appropriate code (32-bit or 64-bit). On 64-bit systems, TrickBot ensured 32-bit version compatibility using Heaven’s Gate techniques, exploiting a Windows 64-bit weakness allowing 32-bit applications to run on 64-bit systems. The executed TrickBot code remained consistent across 32-bit and 64-bit systems, but the execution trigger differed: scheduled tasks on 32-bit systems, and injected svchost processes on 64-bit systems.

September 2019: Alternate Data Streams (ADS) Exploitation

TrickBot operators further enhanced stealth by manipulating Alternate Data Streams (ADS), an NTFS feature in Windows containing file location information. Using ADS reduced TrickBot’s detectability. Malicious code was hidden within macro-laden MS Word files using white font color to conceal JavaScript code.

Infection occurred when users enabled macros, copying the malware to /APPDATA/\Microsoft/Word/STARTUP. A 0-byte file named “stati_stic.inf” was created, but TrickBot used ADS to hide its code within the system. The malware collected computer name, manufacturer, model, and running process names and locations. It also searched for files with .doc, .xls, .pdf, .rtf, .txt, .pub, and .odt extensions, copying itself with the same name but a .js extension to these files, enabling spread across networks, even outside the initial network. This September 2019 TrickBot variant had self-updating capabilities and could download and execute additional malware, storing downloaded files in ADS within the “temp” folder to evade detection.

How to Detect and Remove TrickBot Using Farbar Recovery Scan Tool (FRST)

Given TrickBot’s complex nature and evolution, detecting and removing it requires specialized tools. Farbar Recovery Scan Tool (FRST) is a powerful, free diagnostic tool often used in malware removal. Here’s how to use Farbar Recovery Scan Tool to help identify and potentially remove TrickBot:

1. Identify Infection with Farbar Recovery Scan Tool (FRST):

- Download FRST: Download the appropriate version of FRST (32-bit or 64-bit, based on your Windows system) from a reputable source like BleepingComputer.

- Run FRST: Execute FRST on the potentially infected computer.

- Scan: Click the “Scan” button. FRST will perform a comprehensive scan of your system, generating two log files:

FRST.txtandAddition.txt. - Analyze Logs: These logs contain detailed information about your system’s registry, files, processes, and more. For TrickBot detection, you would look for suspicious entries, particularly in startup items, scheduled tasks, loaded modules, and network connections. While interpreting FRST logs requires expertise, you can seek assistance from online forums or cybersecurity professionals who are familiar with analyzing FRST logs for malware infections. Look for unusual file names, locations in

AppDataRoaming, and services with generic or misleading names as mentioned in TrickBot’s history (e.g., “Service Techno”).

2. Disconnect from the Network:

- Immediately disconnect the infected computer from the network (both wired and wireless). This helps prevent TrickBot from spreading further within your network and isolates it from its CnC server.

3. Patch EternalBlue Vulnerability (MS17-010):

- Since TrickBot has utilized the EternalBlue exploit, ensure your Windows system is patched against this vulnerability. Microsoft released a patch (MS17-010) to address this. Refer to Microsoft’s support page for details and to download the patch if it’s not already installed.

4. Disable Administrative Shares:

- TrickBot and similar malware can spread through network shares, especially administrative shares. Disable administrative shares to limit lateral movement. This is generally done through Group Policy settings in a domain environment or local security policy for standalone machines.

5. Remove TrickBot:

- Antivirus/Antimalware: Use a reputable antivirus or antimalware program to scan your system. Many security solutions are capable of detecting and removing TrickBot. Ensure your antivirus is up-to-date before running a full system scan.

- Manual Removal (Advanced): In some cases, manual removal might be necessary, especially if the malware is resistant to automated removal. This is an advanced process that involves using FRST logs to identify malicious files, registry entries, and processes, and then manually deleting them. This should only be attempted by experienced users or cybersecurity professionals as incorrect manual removal can cause system instability.

6. Change Passwords:

- Because TrickBot steals credentials, change passwords for all accounts accessed from the infected computer, including online banking, email, and domain/local account logins.

Disclaimer: Using FRST and manually removing malware can be complex and potentially risky. If you are not comfortable with these steps, it is highly recommended to seek professional help from a cybersecurity expert or IT support specialist.

By understanding TrickBot’s history, recognizing its tactics, and learning how to use Farbar Recovery Scan Tool, you can take proactive steps to detect and mitigate this persistent and evolving cyber threat. Regularly updating your security software, patching vulnerabilities, and practicing safe online habits are crucial for preventing TrickBot and other malware infections.

Sources:

- bleepingcomputer.com

- malwarebytes.com

- f5.com

- securityintelligence.com

- cyberbit.com

- trendmicro.com

- fortinet.com

- cybereason.com